One of the most characteristic summer visitors to Haachts Broek is undoubtedly the beautiful Golden Oriole (Oriolus oriolus). It is also the only tropical songbird from the family Oriolidae (Orioles and Figbirds) that nests in Europe.

Every year it is exciting to wait for the first song of the Golden Oriole during the period April / May.

In Haachts Broek, the poplar forests are the regular place to hear them sing (read more under "Biotope and way of life").

The arrival of the Golden Oriole in Haachts Broek is always at the beginning of May, but this year I was anxiously waiting. No song was heard for the first few weeks. Last year it was heard earliest on 09/05/2020.

In Haachts Broek, the poplar forests are the regular place to hear them sing (read more under "Biotope and way of life").

The arrival of the Golden Oriole in Haachts Broek is always at the beginning of May, but this year I was anxiously waiting. No song was heard for the first few weeks. Last year it was heard earliest on 09/05/2020.

The call and song of Golden Oriole - copyright Hannu Jännes & Owen Roberts

De eerste verschijning van de Wielewaal aan zijn nest - © Thierry De Bock

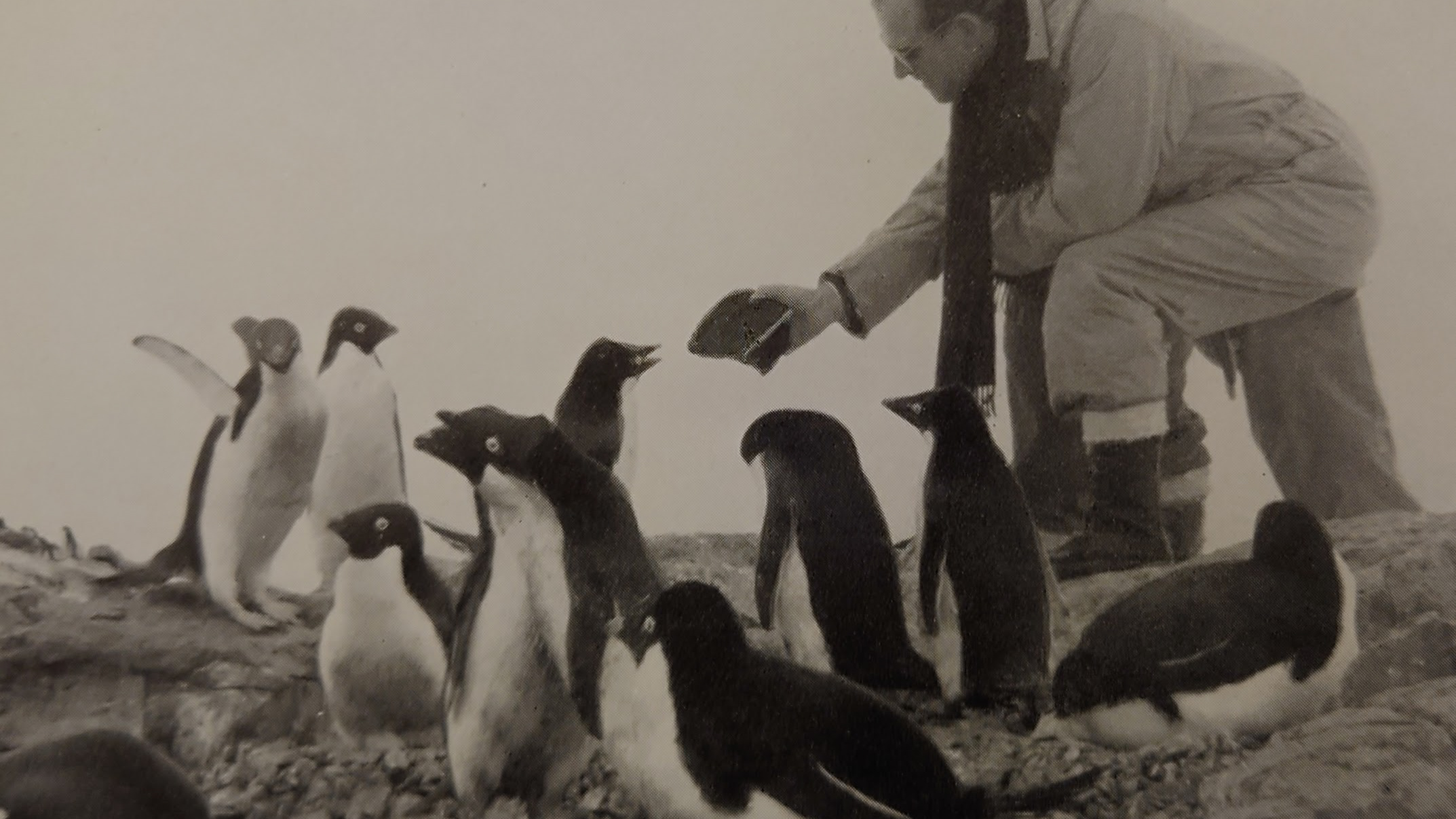

Het voederen van de jongen - © Willem Vannoten

This year it was considerably later, specifically on 27/05 the first specimen was heard. The adrenaline rush in this enthusiastic writer peaked again.

Between the two poplar groves, not even one pair was noticed, but clearly two pairs. On a good morning, a singing battle was heard between two singing posts. Our joy, within the small group of local bird watchers, was extra rewarded when one of our bird watchers, Willem, noticed the special nest of the Golden Oriole. After several weeks of observing the nest, from a distance so that nesting was not disturbed, we noticed the first feeding moments of the young. Through the telescope, we saw three beaks emerging above the nest. Out of consideration to minimise disturbance to the nest, it was decided to "blur" the observations regarding its location. After the first reports of nest-indicating behaviour, we received reports from individuals asking for the exact location of the nest. Better not! This is confirmed when we get the question from a person from East Flanders, who claims to be a passionate birdwatcher. Checking his profile, we find only the Black Crow on his list, whose sightings you can count on one hand. After further investigation, we even come across an advertisement on 2dehands.be claiming to be a bird trader.

Between the two poplar groves, not even one pair was noticed, but clearly two pairs. On a good morning, a singing battle was heard between two singing posts. Our joy, within the small group of local bird watchers, was extra rewarded when one of our bird watchers, Willem, noticed the special nest of the Golden Oriole. After several weeks of observing the nest, from a distance so that nesting was not disturbed, we noticed the first feeding moments of the young. Through the telescope, we saw three beaks emerging above the nest. Out of consideration to minimise disturbance to the nest, it was decided to "blur" the observations regarding its location. After the first reports of nest-indicating behaviour, we received reports from individuals asking for the exact location of the nest. Better not! This is confirmed when we get the question from a person from East Flanders, who claims to be a passionate birdwatcher. Checking his profile, we find only the Black Crow on his list, whose sightings you can count on one hand. After further investigation, we even come across an advertisement on 2dehands.be claiming to be a bird trader.

All that happiness and joy was unfortunately halted when we were overwhelmed by heavy and constant rainfall during the summer. As with many species, this means a negative impact on raising young. Especially for the Golden Oriole, which as a heat-loving species is sensitive to cold and wet weather.

As Golden Orioles lay only one brood per year, it is always a matter of fear and waiting to see how successful they will be. It is make or break.

As for the second pair in Haachts Broek, there is no knowledge of a nest and given the heavy rainfall, we also assume that this pair also did not have a successful brood this year.

So it's a scared wait and see every year due to the changing climate what the Golden Oriole will do.

The only obvious conservation measure is to maintain and create suitable habitats: large areas of moist deciduous forests, near standard orchards.

As Golden Orioles lay only one brood per year, it is always a matter of fear and waiting to see how successful they will be. It is make or break.

As for the second pair in Haachts Broek, there is no knowledge of a nest and given the heavy rainfall, we also assume that this pair also did not have a successful brood this year.

So it's a scared wait and see every year due to the changing climate what the Golden Oriole will do.

The only obvious conservation measure is to maintain and create suitable habitats: large areas of moist deciduous forests, near standard orchards.

Wielewaal vrouwtje bij het nest - © Johan Denonville

Recognition

Showing itself is not their strong suit, but their song brightens up the start of the breeding season and is music to the ears of any bird lover.

Still, we can clearly notice its tropical influence in its colours.

The male is vividly coloured in a black and yellow plumage, red eyes and bill.

In contrast, the female and juvenile are less conspicuous and have more camouflage colours. A yellowish-green back and a greyish-white underside with longitudinal stripes. However, some adult females can show very yellow colouration with faint stripes in the underbelly.

With their elongated size (22-25 cm), they are as large as the blackbird, but more slenderly built.

Males arrive in breeding grounds earlier than females (one week on average) and immediately make their presence known through their singing. A repetitive melodious whistling "wiela-wie-joe" or "duudeljo". The Golden Oriole's song is a clear onomatopoeia or sound imitation of its name. Sometimes from a tree, it lets out a sharp, scratchy "shrèè", which often reminds us of a Jay with a cold.

Still, we can clearly notice its tropical influence in its colours.

The male is vividly coloured in a black and yellow plumage, red eyes and bill.

In contrast, the female and juvenile are less conspicuous and have more camouflage colours. A yellowish-green back and a greyish-white underside with longitudinal stripes. However, some adult females can show very yellow colouration with faint stripes in the underbelly.

With their elongated size (22-25 cm), they are as large as the blackbird, but more slenderly built.

Males arrive in breeding grounds earlier than females (one week on average) and immediately make their presence known through their singing. A repetitive melodious whistling "wiela-wie-joe" or "duudeljo". The Golden Oriole's song is a clear onomatopoeia or sound imitation of its name. Sometimes from a tree, it lets out a sharp, scratchy "shrèè", which often reminds us of a Jay with a cold.

Habitat and lifestyle

Its preferred habitat is alluvial forests.

These are places where rivers or streams have deposited nutrient-rich sediment and where rich undergrowth is strongly present.

As these specific biotopes are less common in Flanders, old poplar woods, standard orchards and large, old parks are a good alternative. It also likes to stay in river areas. The combination of these biotopes makes areas such as Haachts Broek, Werchters Broek and Wijgmaalbroek ideal places to observe this species.

In the high crests, they make a pouch-like nest at the end of the branch. This nest is made like a strongly braided basket of grass stalks, leaves, plant fibres and strips of bark and lined with grass, wool and feathers.

Their braiding technique strongly reminds us of the African Weavers.

They make a new nest every year, but near the old one.

Orioles only stick to one clutch, exceptionally a 2nd clutch may occur. The clutch consists of 3 to 5 white or faintly pinkish eggs with black spots. Egg laying usually starts in June. After 14 days of incubation and after about 2 weeks, the young leave the nest.

Mantling is not uncommon in Golden Orioles. The previous year's young contributes its bit to the family by helping to brood and feeding the new young.

These are places where rivers or streams have deposited nutrient-rich sediment and where rich undergrowth is strongly present.

As these specific biotopes are less common in Flanders, old poplar woods, standard orchards and large, old parks are a good alternative. It also likes to stay in river areas. The combination of these biotopes makes areas such as Haachts Broek, Werchters Broek and Wijgmaalbroek ideal places to observe this species.

In the high crests, they make a pouch-like nest at the end of the branch. This nest is made like a strongly braided basket of grass stalks, leaves, plant fibres and strips of bark and lined with grass, wool and feathers.

Their braiding technique strongly reminds us of the African Weavers.

They make a new nest every year, but near the old one.

Orioles only stick to one clutch, exceptionally a 2nd clutch may occur. The clutch consists of 3 to 5 white or faintly pinkish eggs with black spots. Egg laying usually starts in June. After 14 days of incubation and after about 2 weeks, the young leave the nest.

Mantling is not uncommon in Golden Orioles. The previous year's young contributes its bit to the family by helping to brood and feeding the new young.

Its diet consists mainly of insects such as, moths and caterpillars, spiders and snails. The hairy caterpillars of the well-known processionary caterpillar is a tasty delicacy for the young. These are fed whole to the young.

In late summer, this is supplemented by the sweet taste of cherries, berries and pears.

The food situation is thus an important factor for the Golden Oriole. Due to the caterpillar peak falling earlier, the Golden Oriole too often misses its chance because it arrives too late as a rangefinder in the area.

So this may be one of the causes of its decline in the last 10 to 15 years.

In late summer, this is supplemented by the sweet taste of cherries, berries and pears.

The food situation is thus an important factor for the Golden Oriole. Due to the caterpillar peak falling earlier, the Golden Oriole too often misses its chance because it arrives too late as a rangefinder in the area.

So this may be one of the causes of its decline in the last 10 to 15 years.

Dispersion of the Oriole in the world. Red zone is its presence during the summer period, while the pink zone is its wintering grounds.

Distribution and numbers

The Golden Oriole occurs during the breeding season (late April/May to Aug/Sep) in Belgium and in the Netherlands.

Its occurrence in Europe extends from the southern part of England and Sweden to south-western Siberia (see distribution map).

In late July, they return to their wintering range that runs from central to southern Africa.

Its occurrence in Europe extends from the southern part of England and Sweden to south-western Siberia (see distribution map).

In late July, they return to their wintering range that runs from central to southern Africa.

Red List

Regarding its status on the IUCN Red List, the Golden Oriole appears in the 'not threatened' category.

Noteworthy is the difference in category with the Red List of Flanders (endangered) versus the Netherlands (vulnerable). In turn, this is evident in the difference in breeding population.

The Netherlands scores for the 2013-2015 period with a population of 1,700 to 2,900 individuals, while Flanders has to make do with less than half (850 to 1,450) for the 2013-2018 period.

Noteworthy is the difference in category with the Red List of Flanders (endangered) versus the Netherlands (vulnerable). In turn, this is evident in the difference in breeding population.

The Netherlands scores for the 2013-2015 period with a population of 1,700 to 2,900 individuals, while Flanders has to make do with less than half (850 to 1,450) for the 2013-2018 period.

A vistit to RBINS

In November, I visited the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences (RBINS) in Brussels. It is mainly known for its renovated museum with its wonderful collection of dinosaurs, but people sometimes quickly forget the many scientists who are busy behind the scenes.

As part of my article, I contacted curator Pauwels, who gave me a tour of the shop floor.

As soon as we got to the first floor, the collections manager Sébastien brought an intact preserved oriole's nest (see photo below). Up close, I could admire with my own eyes the weaving skills of this "tropical bird". The nest is so tightly woven that hardly any light gets through.

Collecting the eggs, I note that a small opening was brought in. Sébastien tells me that this is standard practice to suck out the contents of the eggs through the opening after examination. The eggs are then treated with a product for conservation. The eggs show a beautiful and unique Dalmatian pattern. The many collections are inventoried by species, place and date. For instance, I notice that the collection predates World War II and that this find is from St-Job-in-'t-Goor.

As part of my article, I contacted curator Pauwels, who gave me a tour of the shop floor.

As soon as we got to the first floor, the collections manager Sébastien brought an intact preserved oriole's nest (see photo below). Up close, I could admire with my own eyes the weaving skills of this "tropical bird". The nest is so tightly woven that hardly any light gets through.

Collecting the eggs, I note that a small opening was brought in. Sébastien tells me that this is standard practice to suck out the contents of the eggs through the opening after examination. The eggs are then treated with a product for conservation. The eggs show a beautiful and unique Dalmatian pattern. The many collections are inventoried by species, place and date. For instance, I notice that the collection predates World War II and that this find is from St-Job-in-'t-Goor.

After studying and having a photo shoot of the collection, the scientific duo takes me further to the collection of stuffed birds. All sorts and numbers of stuffed birds comes across as very lugubrious, but it is still an impressive sight. Curator Pauwels tells me that the oldest collection dates back to 1800.

The search for the oriole collection is not easy and soon I notice that it does not stop at one floor. After searching through a few rooms, we find the collection of stuffed Orioles.

The search for the oriole collection is not easy and soon I notice that it does not stop at one floor. After searching through a few rooms, we find the collection of stuffed Orioles.

My dear readers, it may seem strange, but to admire so closely the plumage of this beautiful species still gave me considerable warmth. It may also be strange for me to want to see this species up close at the institute, but to study this so close there is no other option.

The stuffed collection pictured comes from the noble collector, Baron Maximilien de Viron, and was captured in June 1909. Unfortunately, these specimens could not breed that year. How unfortunate that this bird was caught, but back then the full awareness of bird trapping for collection was not as much of a hot-topic as it is now. On the other hand, this was the way to study birds. Still, it is a good thing that there are much better methods with better results at the natural science level.

The stuffed collection pictured comes from the noble collector, Baron Maximilien de Viron, and was captured in June 1909. Unfortunately, these specimens could not breed that year. How unfortunate that this bird was caught, but back then the full awareness of bird trapping for collection was not as much of a hot-topic as it is now. On the other hand, this was the way to study birds. Still, it is a good thing that there are much better methods with better results at the natural science level.

Het gewoven nest van de Wielewaal

De collectie eieren

Een vondst van meer dan 80 jaar geleden

Vrouwtjes Wielewaal

Mannetjes Wielewaal

Acknowledgements

I would particularly like to thank the following people, Johan Denonville, Willem Vannoten and Thierry De Bock, for sharing their photos. As also my thanks to Jens D'Haeseleer with his beautiful artwork that I am happy to show as the main photo.

In addition, my thanks go to the curator, Olivier Pauwels, and collection manager, Sébastien Bruaux, at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences in Brussels for their warm welcome when I visited their archives. Thanks to them, I had the chance to admire the many floors of collections of stuffed birds.

I also wish to thank you, my readers, after reading my first article on my personal blog.

Therefore, I hope this will encourage you to go out into nature more in search of nice sightings and species.

In addition, my thanks go to the curator, Olivier Pauwels, and collection manager, Sébastien Bruaux, at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences in Brussels for their warm welcome when I visited their archives. Thanks to them, I had the chance to admire the many floors of collections of stuffed birds.

I also wish to thank you, my readers, after reading my first article on my personal blog.

Therefore, I hope this will encourage you to go out into nature more in search of nice sightings and species.

Keep on birding!